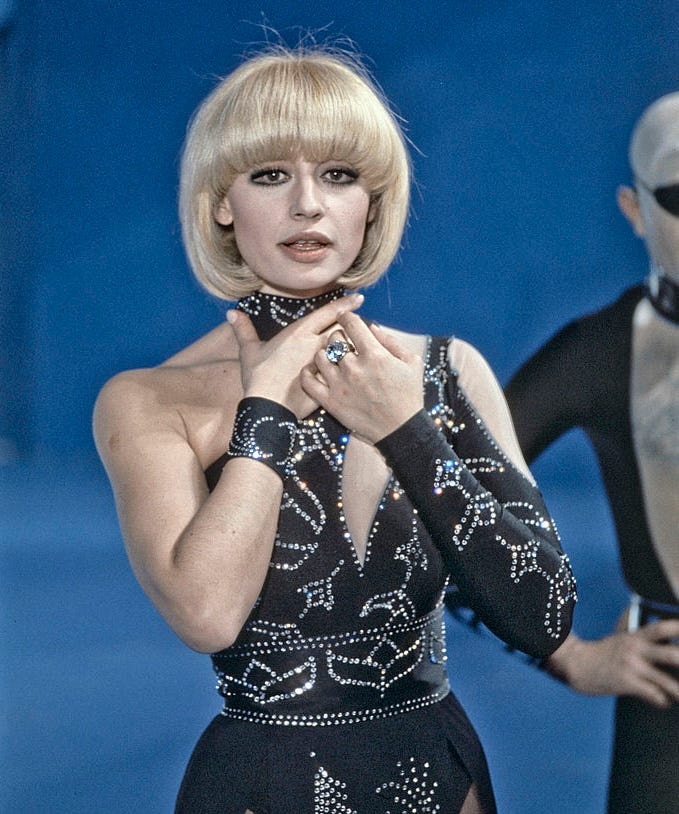

A Deep Dive into Raffaella Carrà: Her Costumes

Raffaella Carrà’s costumes made costume-design history.

1983.

In second grade, I had two daily habits right after I came out of school. The first was to stop by the window of the local record shop called “L’Angolo Della Musica” to check the latest releases on display. The second was to rush home to catch the last part of “Pronto, Raffaella?”, the daily hybrid of game show, talk show and variety hosted by Raffaella Carrà. As I was sitting two feet away from the TV screen (which was something my mom always reproached me for), along came Raffaella and a group of male dancers singing “Caliente Caliente” in black leather and bondage outfit that were a clear reference to the gay leather/Tom Of Finland style universe. My mom behind me was also fascinated by the performance and was hypnotized by such a contrast of “dark” costumes and the joyful tune Raffaella was singing. It was the beginning of my fascination with the aesthetics/music combo that just in those years was making history in Italian culture.

Disco Bambino